Amid the relentless procession of events, there is something quietly radical in the refusal to let meaning fix itself, to allow instead for ambiguity and drift. In generative music, this manifests not as abdication, but as a vigilant sculpting of possibility—an act best witnessed in the slow blossoming of Brian Eno’s generative works, where structure emerges, not by design, but by the playful interplay of constraint and chance.

The use of weighted probabilities in MAX/MSP or SuperCollider—such as assigning a 30% likelihood to a given note event, while redistributing the rest amongst silences or alternatives—offers a kind of invitation: not into chaos, but into a continuously shifting near-order. Certain algorithms construct chains of recurrence, using Markov processes to modulate melodic or textural outcomes. Here, the music finds itself in the interstice between plan and coincidence, each repetition slightly skewed by the logic of weighted deviation, never quite identical to its predecessor.

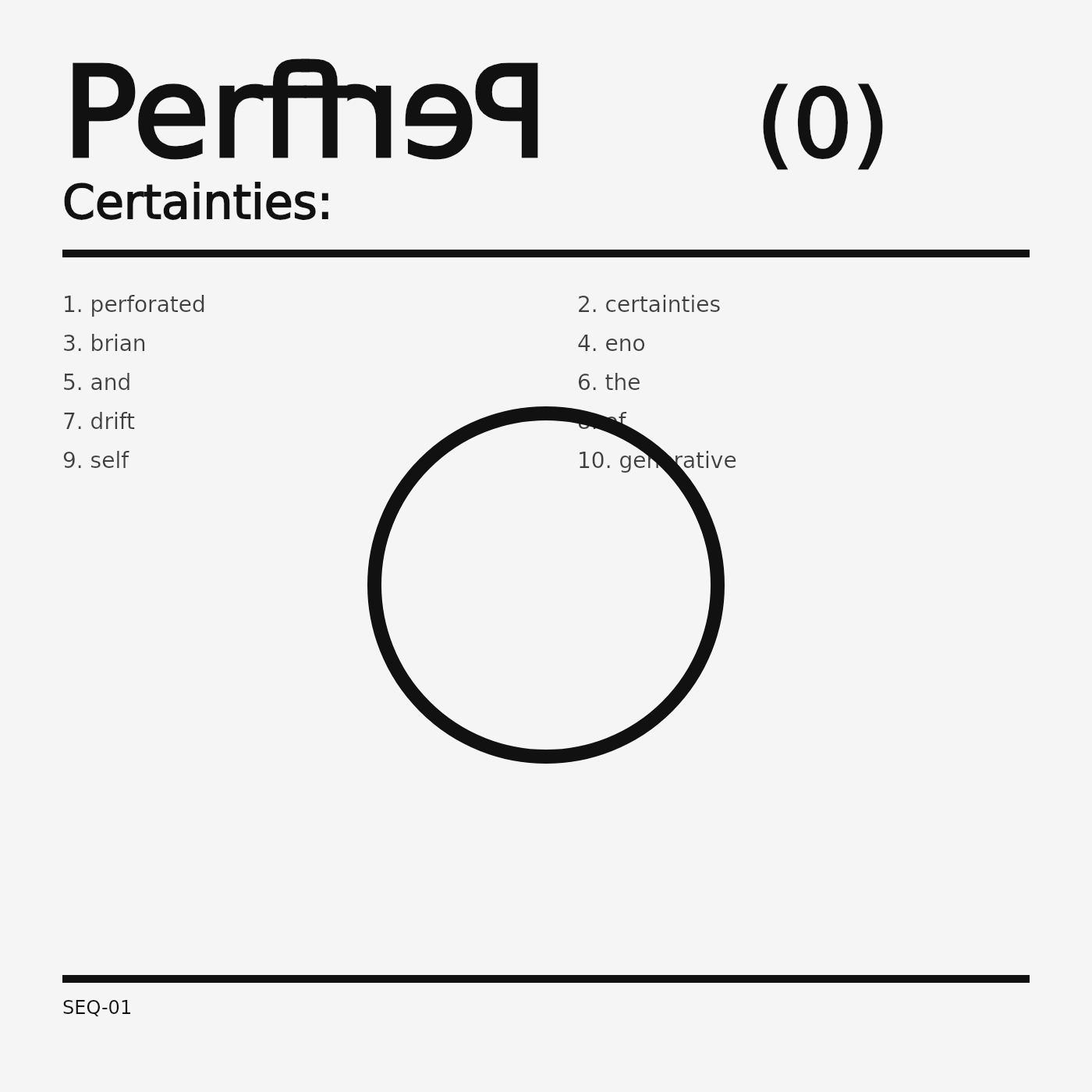

What makes such music unsettling is its resistance to closure. There is no safe return, no cyclical assurance. Instead, the material unfolds as an ongoing negotiation with the unknown. The listener’s sense of agency, like the composer’s, is subtly requisite—they must attend, with both vigilance and patience, to the possibility that in the next moment, the order might simply collapse or reconstitute itself otherwise. In this, generative music models something uncomfortably familiar: the porousness of our own certainties, the contingency of control. It enacts, without fuss, a perpetual reminder that structure is always vulnerable to error, or—more creatively—to reconsideration.

James Whitfield